Unharvested Justice: Commemorating Mendiola Massacre

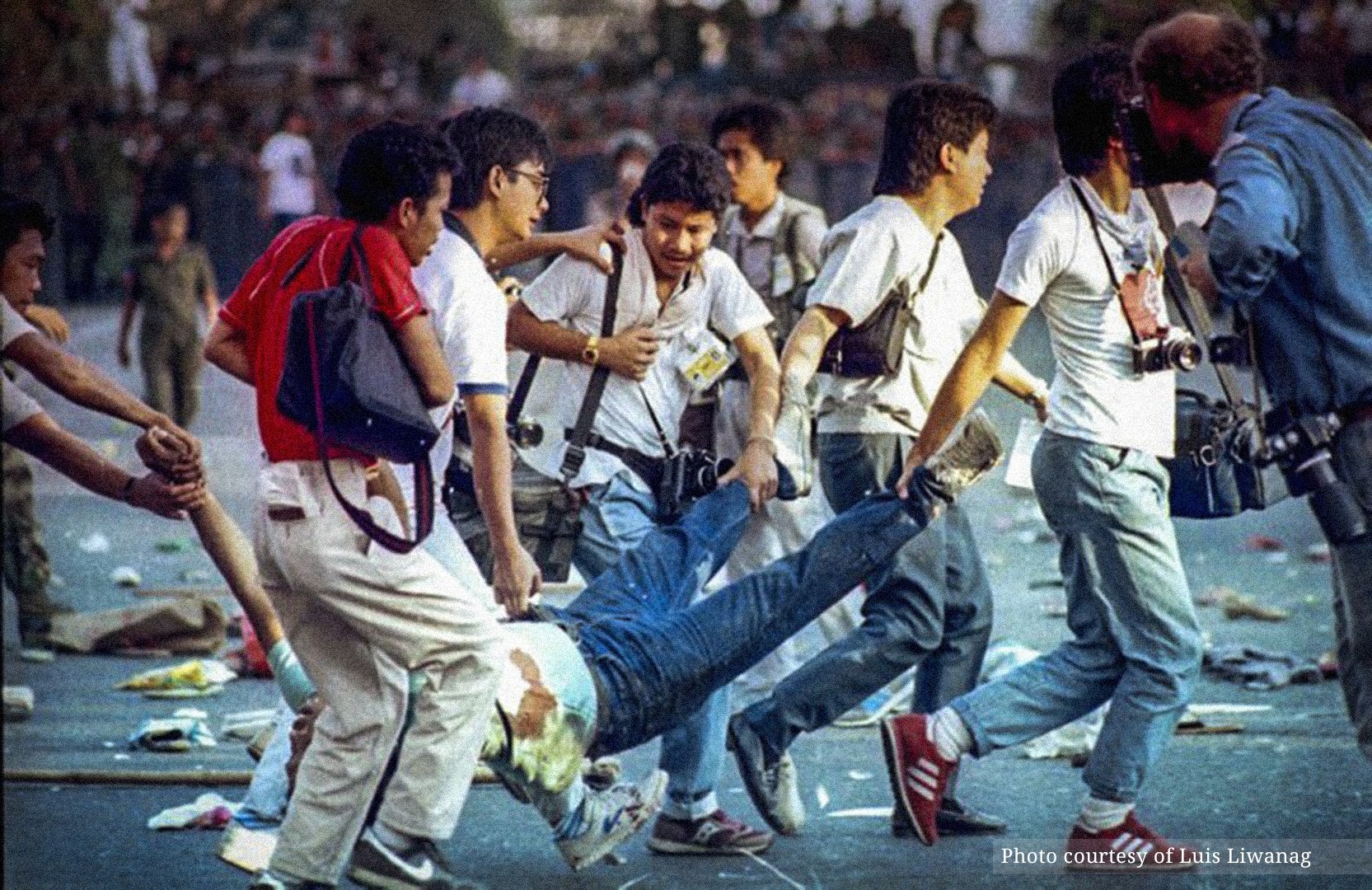

A supposed peaceful mobilization, which took place on Mendiola Street, had one of the most violent turns in Philippine history, taking the lives of 13 farmers on January 22, 1987.

37 years have passed and today, we commemorate the brave lives that the Mendiola Massacre has taken and changed for the worse.

Thousands of farmers and peasants hoped that the Malacañang, headed by the then newly-elected President Corazon Aquino, would hear their echoes of justice for their livelihood, but instead, they were met by authorities. State forces fired on 10,000 to 15,000 farm workers and peasants, who only strived and fought for a fair agrarian reform and sustainable wages.

Here is everything you need to know about the timeline developments of the Mendiola Massacre:

January 22, 1987. From Liwasang Bonifacio to Mendiola, the Kilusang Magbubukid sa Pilipinas (KMP) staged a peaceful protest to address the looming state of land reform in the country. Giving land to the tillers, abolishing land retention of landlords, and stopping amortization were the masses’ demands. This day also marked the seventh day of the demonstrators staying in front of the then Ministry of Agrarian Reform (currently known as Department of Agrarian Reform), insistent on their need of a genuine agrarian reform. The former KMP President Jaime Tadeo emphasized that the land reform program that the Congress would provide, under the new Constitution, is not genuine as Congress were hegemonized by landlords and businessmen.

As tension arose, the Western Police District (WPD), Integrated National Police (INP), and the Marine Civil Disturbance Control Battalion gunned down the rallying masses, consisting of farmers and other multi-sectoral networks, who only demanded a genuine land reform from the administration at the time. In the aftermath, a total of 13 farmers were declared dead, 39 obtained gunshot wounds, and 20 suffered from minor injuries.

January 23, 1987. A day after the massacre took place and as per the House Committee on Human Rights, Aquino created the Citizens’ Mendiola Commission, headed by the retired Supreme Court Justice Pedro Abad Santos, to conduct an investigation on the incident and to assure that justice will be served to the victims, as well as to the survivors.

February 16, 1987. Two videotapes were given to the Commission as evidence of the gruesome act. The said tapes showed state forces openly firing at the protesters.

February 27, 1987. Administrative charges were filed against state authorities who appeared either in the submitted video footage or photographs. Instead of focusing on the human rights violations committed by military and police elements, Tadeo, who was a key person in the movement, faced trumped-up charges under the guise of infringing the Public Assembly Act, which mandates people to have a permit before staging their dissent.

March 2, 1987. The Commission disbanded without taking any necessary actions regarding the massacre, apart from proposing the filing of criminal charges against all commissioned officers involved during the peasant protest, as well as marchers for “carrying deadly or offensive weapons” whose identities were never proven, and for the government to give adequate compensation for the deceased and injured due to the incident.

July 27, 1987. Petitioners, hailing from the victims of the Mendiola tragedy, filed a letter of demand for compensation from the government.

January 20, 1988. Almost a year after the event, the victims remained deprived of compensation hence, they resorted to filing a class suit against the state.

May 31, 1988. The Manila Regional Trial Court dismissed the class suit that was filed by the families of the survivors and victims against the government, as well as police and military officials, due to the ruling that the suit is against the Republic of the Philippines and the State did not consent to be sued.

March 19, 1993. The Supreme Court indorsed the decision of the lower court, emphasizing the principle of immunity of the government.

Decades have passed and the 13 people who were ruthlessly killed in the grim event never got a glimpse of justice. Their names shall be remembered as the fight continues; Adelfa Aribe, Danilo Arjona, Ronilo Domanico, Dante Evangelio, Bernabe Laquindanum, Roberto Yumul, Leopoldo Alonzo, Dionisio Bautista, Roberto Caylao, Sonny Boy Perez, Vicente Campomanes, Angelito Gutierrez, and Rodrigo Grampan.

Ever since then, militant groups and farmers nationwide annually gather to commemorate what happened in Mendiola, seeking the justice that has been evasive. Their continuous suffering from the lack of genuine agrarian reform, forced land-grabbing from corporations, red-tagging state surveillance, and the outright killings is a long stem of injustice that is barely given light. This is a fight that they have been enduring whilst remaining defenseless.

Landlessness remains as those in power remain ignorant to the real issue at hand. Reform acts, specifically the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) which was Aquino’s not-so-temporary fix response to the Mendiola bloodshed, remain counterproductive as it does not address the actual roots of why farmers remain shackled to poverty despite working endlessly amidst the growing industrialization and natural calamities. Meanwhile, the Genuine Agrarian Reform Bill (GARB), which aims for a fair land distribution, remains stagnant in the legislative houses as if there is no grave need of an actual land reform from the past decades.

Let this grim reminder uncomfortably push us further in never forgetting a speck in a heap of injustices that the masses are facing.

Photo slider by Luis Liwanag